In the previous Become an Investor post I gave an introduction to stocks and bonds. Understanding how these instruments work is crucial and required in order to start investing. However, although having the knowledge and experience gives you an advantage, I still went on to say that picking stocks is time consuming, risky, and not the optimal way to invest for beginners.

To be fair, I’m not against taking even riskier positions, but I’d say that doing so should be a conscious decision after you know what you’re doing and what your options are. In other words: digest the Become an Investor series and never stop learning.

So, first thing’s first – let’s see what an index is and then we’ll cover how to use one to support your investment strategy.

What is an Index?

The word index has various meanings, but it usually represents a statistical measure of something. In the context of investing or financial markets in general, it’s called market index and it measures the changes in a hypothetical portfolio representing a specific (or not so specific) market or a part of it.

To illustrate and explain better, imagine that you would like to know the behavior of the petroleum industry in the recent 3 years. That implicitly means that you’re interested in the performance of the leading companies in the field. Of course, you could do a research for each individual company on your own, but an easier way to understand it is to check the NYSE Arca Oil Index and select 3Y.

What ^XOI (the ticker symbol for the above mentioned index) shows is the performance of the oil industry through a value based on the prices of the underlying stocks. Have in mind, this value is an indicator, not a number that you could convert into a currency. In other words, you shouldn’t be concerned about the current value of an index, but the relative value representing its change comparing it to the index value at some point in the past.

As we can see in the picture, the index value is lower than it was 5 years ago – and that tells us about the performance about the specific industry or market.

But as an advocate of diversification, this index is not broad enough for my investment profile. Of course, its purpose is to track a narrow field, so I’m not saying that it’s “bad” (whatever that would mean), but I am saying that I wouldn’t use it as a benchmark for my portfolio. Maybe I would if I knew more about the industry, but that’s currently not the case.

So let’s explore some other indexes before going further.

Market Index – Examples

Dow Jones Industrial Average

In 1896, Charles Dow created the first index – the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA), sometimes referred to as the Dow. Today, this index shows the performance of 30 large publicly traded American companies (such as Cisco, Walmart, Microsoft, Coca Cola, Walt Disney, etc. – click here for full list).

Unlike the index previously described, the DJIA is not bound by an industry, but by other factors, one of which is geography – all the companies are based in the United States. The phrase “the market is up” can mean an increase in the value of the Dow for that day.

The value is calculated differently for different indexes, but in this specific case, it’s the sum of the price of a share for each component company divided by the “Dow Divisor” (details withheld, but the keyword is there for the interested). This is slightly different that how the value of DJIA was calculated back in 1896, which was a simple arithmetic average: the sum of the stock values for each company divided by the number of companies in the index (initially 12).

But talking about diversification, although the DJIA is a good indicator of the performance of the US market, it tracks only 30 companies. All of them with large market cap, but still only 30. Another index that can be used as a measure for the American market is the Standard & Poor’s 500, abbreviated and mostly known as the S&P 500 index.

S&P 500

Directly from Investopedia:

The S&P 500 is designed to reflect the U.S. equity markets and, through the markets, the U.S. economy. It’s widely regarded as the best single measure of large-cap U.S. stocks, and, like the Dow, has become synonymous with “the market.”

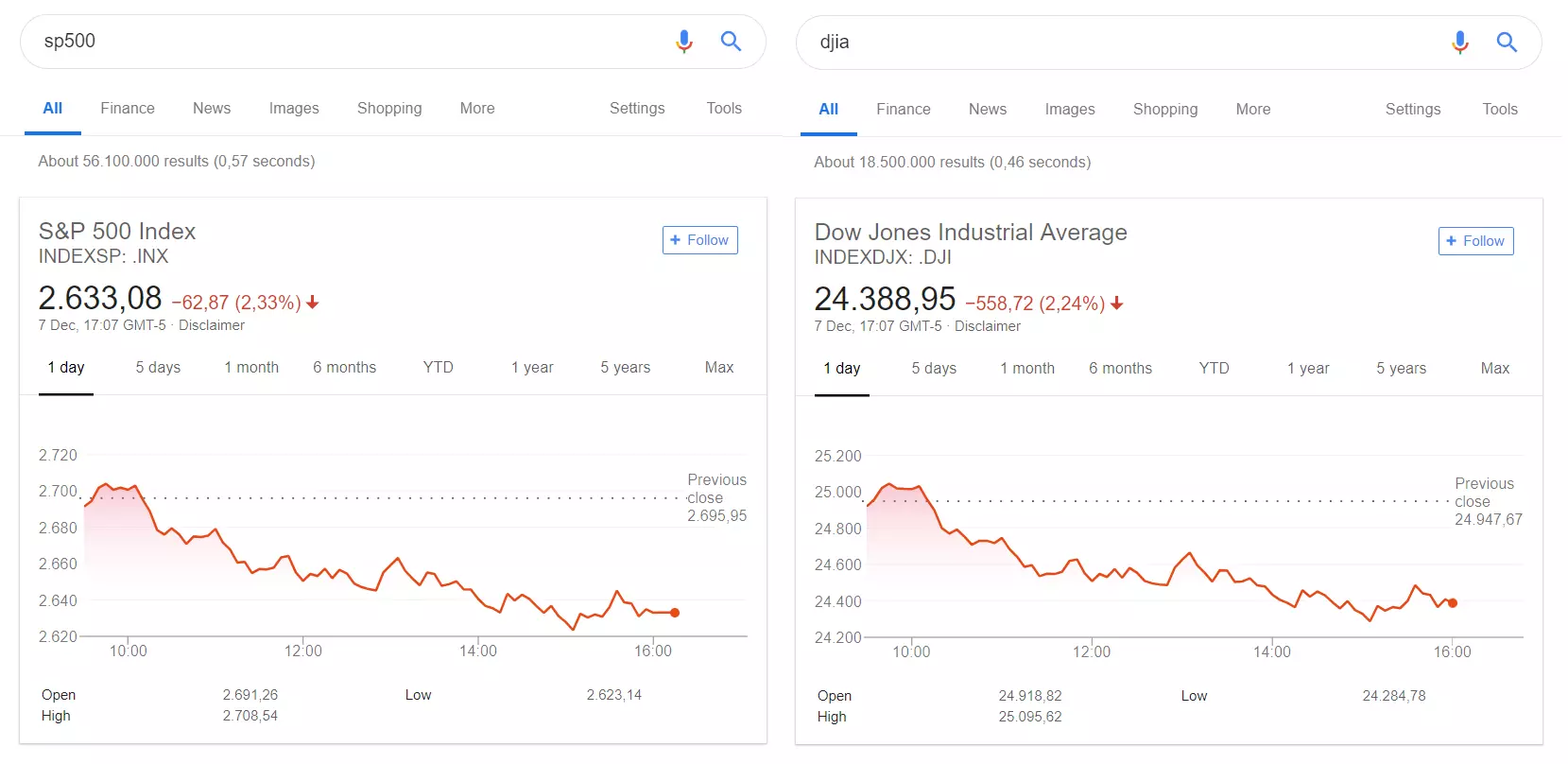

And indeed, if you google the words “sp500” and “djia”, you will get two charts that look pretty similar to each other, regardless of which period you chose.

Remember, the numbers 2.633,08 and 24.388,95 don’t show us that the one has “higher value” than the other – they are calculated differently, with different component companies, for different indices. However, although the absolute numbers don’t tell us much, the 2,33% and 2,24% do. They tell us that the US stock market went down around 2,3% in the last day.

The S&P 500 tracks stocks from 500 large cap companies and covers all major areas of the US economy. Unlike the DJIA however, it’s a capitalization-weighted index, which means that the companies with larger market cap have higher percentage weights, while the companies with smaller market cap have smaller weights.

For example, Apple’s weight in the index is higher than 4% and Foot Locker’s is 0,02%. Of course, these values may and will change over time as the companies’ market caps change, which leads me to one of the most important characteristics of the indexes. They all have specific criteria for including companies and if a company in the index fails to meet this criteria, it won’t “make it” after the next review.

That means that if you decide to use an index as a benchmark for your portfolio, it will automatically filter out companies that under-perform.

This is something that you can’t get while picking individual stocks! However, it’s still not risk free. The sole nature of the economy (which is cyclical), a market crash, or a recession, all cause an index to go down. So although you’re safe from companies defaulting, you can still lose money betting on any country’s economy.

But remember the saying “you only lose when you sell”. The good news is that the global market always recovers through time1, but that is a story for another time.

Other indices

Have in mind that this was a high level overview for both DJIA and S&P 500 as the purpose of this post is not to introduce you with the indices in full detail, but to explain what they are and how to use them to build your portfolio. So we’re just a paragraph short of understanding how to do so, but let’s first go through a few more indices, just to give you a perspective of the various measures available.

The Nasdaq Composite Index (representing 3000+ stocks trading on the Nasdaq exchange), Nasdaq 100 (tracking the largest 100 non-financial companies on Nasdaq), MSCI World (tracking >1500 stocks from developed countries all around the world), Wilshire 5000 (representing all publicly traded US companies – small, mid, and large cap), Russell 2000 (tracking small cap US companies), MSCI AEFE (tracking the developed markets outside US and Canada – in Europe, Australia, and Far East), FTSE 100 (tracking the 100 largest companies trading on the London stock exchange), MSCI Europe ex UK Index (self-explanatory – tracking developed EU markets, excluding the UK), Nikkei (tracking top companies trading on the Tokyo stock exchange), MSCI Emerging Markets Index (tracking 23 economies from developing countries), EURO STOXX 50 (tracking 50 large Eurozone companies), and much much more! Wikipedia has a list of all the commonly used stock market indices.

What I’m trying to convey is: regardless of whether you’re interested to segment your investments by field, industry, country, region, market cap, or how developed a market is, you will find an index or a combination of indices that will suit your needs.

And let’s not forget about them, there are also indices for bond markets, so if you’re more into the fixed income securities or want to balance your portfolio, you’re also covered. How you choose your asset allocation is a topic for a future part of this series. For now, let’s focus on how to invest using the knowledge you gained so far.

Index Investing

Sorry, you can’t invest in an index.

I keep building anticipation for it and I pull it back mercilessly each time… Not this time though!

While it is true that you can’t invest in an index, because as mentioned above – it’s a measure of a market’s performance and its value can’t be converted into USD or EUR, you can still use indices to build your portfolio. And that is known as index investing.

Okay, let’s start slowly.

Index investing is a strategy investors use to invest in a specific market by tracking the performance of an index, usually passively. Passively means that there is no active portfolio management (frequent buying & selling, rebalancing, or picking stocks) and usually, but not always, done through a DCA (dollar cost averaging – an investment strategy of making periodic contributions to a portfolio, on a fixed day with a fixed amount). More on DCA later in the series.

So, no “timing the market” and no “beating the market”. This strategy is synonymous with matching the market, at least the one you choose to match. And let’s not forget that beating the market is impossible to do continuously, which means that there are no active portfolios that generated better returns than “the market” (DJIA or S&P 500) on the long run. I will discuss this in much detail later in this series.

Now, how do we match the market? The way index investing works is through index funds or ETFs (exchange traded funds). They’re both replicating the performance of the underlying index, thus generating returns such as the index itself would, if we were able to invest in it. Basically, the companies allowing index investing attempt to create a portfolio based on the components of a specific index, thus giving a chance to us, investors, to invest in the market itself through their index funds or ETFs, for a small fee.

Considering the low fees, broad diversification, and somewhat predictable behavior, index investing is the best and safest long-term investment strategy, proven to outperform active portfolio management on the long run.

What’s next?

Now, I’m slowly approaching both 2000 words and 6 AM, so I will leave out the details regarding index funds and ETFs for the upcoming posts of the series. For now, it’s more than enough to understand what a market index is and that there are ways that allow us to bet on the market’s overall performance.

Digest the knowledge and learn slowly, even do your own research after each post. This way of structure and comprehensiveness is the way I would have liked to learn about investing myself – in a step by step, structured, and self-contained guide.

Actually, I’m not aware of any introduction to investment online structured in a way that assumes the reader has absolutely no knowledge about investing and starts from ground zero. If you stumbled upon this post and found some terminology confusing, I’d recommend checking out part 1, where I explain what investing is and what it isn’t, and part 2 where I give an introduction to stocks and bonds.

And don’t forget, becoming an investor is not an easy path, so make sure to digest the current material before going forward. And I’ll make sure to provide all the required knowledge as clear as possible. For example, seems that I need to cover two crucial things in regards to index investing:

- What exactly is a passively managed portfolio and why a passive index investing strategy is better and safer than active portfolio management?

- What exactly are index funds and ETFs, how to read and understand them, and how to pick the right ones?

Sounds like a plan for parts 4 and 5!

See you there.

Previous Become an Investor post: Introduction to Stocks and Bonds

Next Become an Investor post: Mutual Funds & Index Funds

PayPal.me/MonkWealth

PayPal.me/MonkWealth