How does becoming an investor feel? I must admit that I’m a bit jealous that you’re going through the basics for the first time – I remember the process as lots of fun, gaining knowledge that makes you see the world from a different perspective. As I said in the first Become an Investor post: once you learn about investing there may be no going back.

In the previous post you learned about index investing. It was more in the form of scratching the surface, but it introduced market indices – the vehicles behind broadly diversified portfolios representing the economy. You also learned that an index is just an indicator and not a security. That means that its value has only relative sense (compared to a previous point in time), so you can’t invest in the index itself. If you’re confused about anything said until now or feeling like I’m going too fast, reading the Introduction to Index Investing is the smartest first step you can take.

Now, although the indices are just indicators and not securities, there are ways to couple your portfolio performance with the performance of a particular index (or more) through index investing. This can be achieved through so-called tracker funds, or just trackers, which are mutual funds who “track” the performance of an index.

Before going into the details, maybe it’s best to explain what a mutual fund is.

Mutual Fund

Let’s take another step back, which we usually follow-up with multiple steps forward, and forget about index investing and index funds. Let’s explain the more general concept of mutual funds first. So, what are mutual funds?

Directly from Investopedia:

A mutual fund is an investment vehicle made up of a pool of money collected from many investors for the purpose of investing in securities such as stocks, bonds, money market instruments and other assets.

Basically, it is an investment fund that invests its investors’ money into certain securities, usually stocks and bonds. The portfolio is managed by the fund itself with the goal to produce capital gains for the fund’s investors. Regarding their portfolios, the mutual funds can differ in various ways, one of which is their type. A mutual fund can be a bond fund, an equity fund, a money market fund, etc., but they’re not restricted to a single type and can also be “balanced” – offering a managed portfolio holding multiple types of securities.

A mutual fund is not just an investment fund, but also a company. When an investor invests in securities through a mutual fund, he is actually buying shares in the fund. That means that he has ownership in the fund’s assets, which are actually the securities in which the fund allocates the investors’ money. And if you think about it, you’ll realize that the value of the fund itself is based on the performance of the securities the fund invests in.

So, if buying a share in a mutual fund is almost the same as buying a share in any company, why would we want to use funds for investing instead of just buying stocks?

Well, unlike other companies, which may have different types of business models (product / service / whatever), the mutual fund’s model is making profit out of investing in various securities, including stocks. That means that when you put your money in a mutual fund that manages a stock portfolio, you end up owning shares in various companies automatically. So, the key difference, and main reason, to go with funds is diversification. That means that you can be more comfortable with your investments, as diversifying has the inherent benefit of taking away the risk of losing everything if your company of choice, for example, defaults. I’d be way more comfortable having $100k distributed through 500 different companies, than the same amount invested in H&M. Compare what happens when the single company goes down in both cases. Of course, diversification will also mean less gains if a single company sky-rockets, but which other-person’s business you’d believe that much to put all your money in it? Me neither.

Basically, the advantage of mutual funds is that you put your money in and let professional management take care of your portfolio. For this service, of course, you pay a fee. However, the costs for owning mutual funds are pretty low, but it depends on the fund. The expenses are usually annual and as a percentage of the investor’s portfolio value, and some funds also have deposit and withdrawal fees.

These expenses are less than 1% of the capital invested (usually 0,25% to 0,5%) and are used to cover the operational costs of the fund. And when I say “less than 1%”, I mean: “if you need to pay 1%, run!”. In investing it’s important to remember that you’re in it for the long-term. That means that any value you lose in fees is a value that won’t grow through the magic of compounding by being invested.

Just to illustrate what I mean by long-term. Let’s say a guy started investing 30 years ago, in December 1988, and did dollar-cost-average (DCA) with $1000 per month. That means that today he’d have 360000$ invested in total. However, if he paid 1% management fee and 1% deposit and withdrawal fees (0,5% each), he’d only have 352800$ invested. Not that $7000 make that big of a difference over 30 years, especially when you already built wealth in the hundred thousands, but I’d rather be $7k wealthier than not even noticing where they went.

But I mentioned the word compounding… Although 360000$ and 352800$ are the amounts invested, the amounts generated during the period will prove the point way more clearer. The $360k invested will grow to 1,581,349$ over the 30 year period, while the $352k will grow only to 1,549,722$. That’s more than $30k thrown away on fees!

But instead of being dramatic and cherry-picking the best and worst case scenarios by comparing a non-existent no-fee fund with a high-fee fund, I’ll just leave you with the most important take-away:

Be mindful of funds’ expense ratios.

Actively VS passively managed fund

Lastly, the funds can be actively or passively managed. Active management means that the fund tries to beat the market, by outperforming some market benchmark, such as an index, using their investors’ money. That makes active management more complicated, as it may also include more advanced strategies than just buying shares (such as shorting, arbitrage, writing options etc.). Of course, this doesn’t require any investor involvement, but makes the management fees higher.

The interesting thing is that every year many actively managed funds outperform their target benchmarks, but no actively managed fund outperformed its target benchmark every year. In other words and in the most simplified manner possible: beating the market consistently is close to impossible.

It’s a popular saying in the FIRE community that the only person who is getting richer through active portfolio management is the portfolio manager. You (and I as well) don’t have to agree with this 100%, but should be able to see the long-term advantage of investing in passively managed funds.

But this deserves it’s own section.

Index Funds

Unlike the actively managed ones, which try to outperform an index, the passively managed funds are simply tracking an index. That means that their performance will always be in line with the index’s performance, which is achieved by buying the securities in the particular index.

Simply put: an index fund is a special type of mutual fund that tracks the performance of an index.

As mentioned in the previous section, the portfolio that an index fund manages would consist of the components of a certain market index. For example, if an index fund tracks the S&P 500, it would ideally have holdings in all companies from the index and in the same proportion. However, the tracking may not be perfect, so there may be some (small) differences in the performance of an index fund and the index itself. The reasons for this difference are various and include: using a representative sample of the index’s components instead of all the securities, using a slightly different weighting than the index itself, or even the fund’s expense ratio itself (as explained above – higher fees will make your portfolio smaller and thus performing worse than the benchmark). By the way, this is called a tracking error.

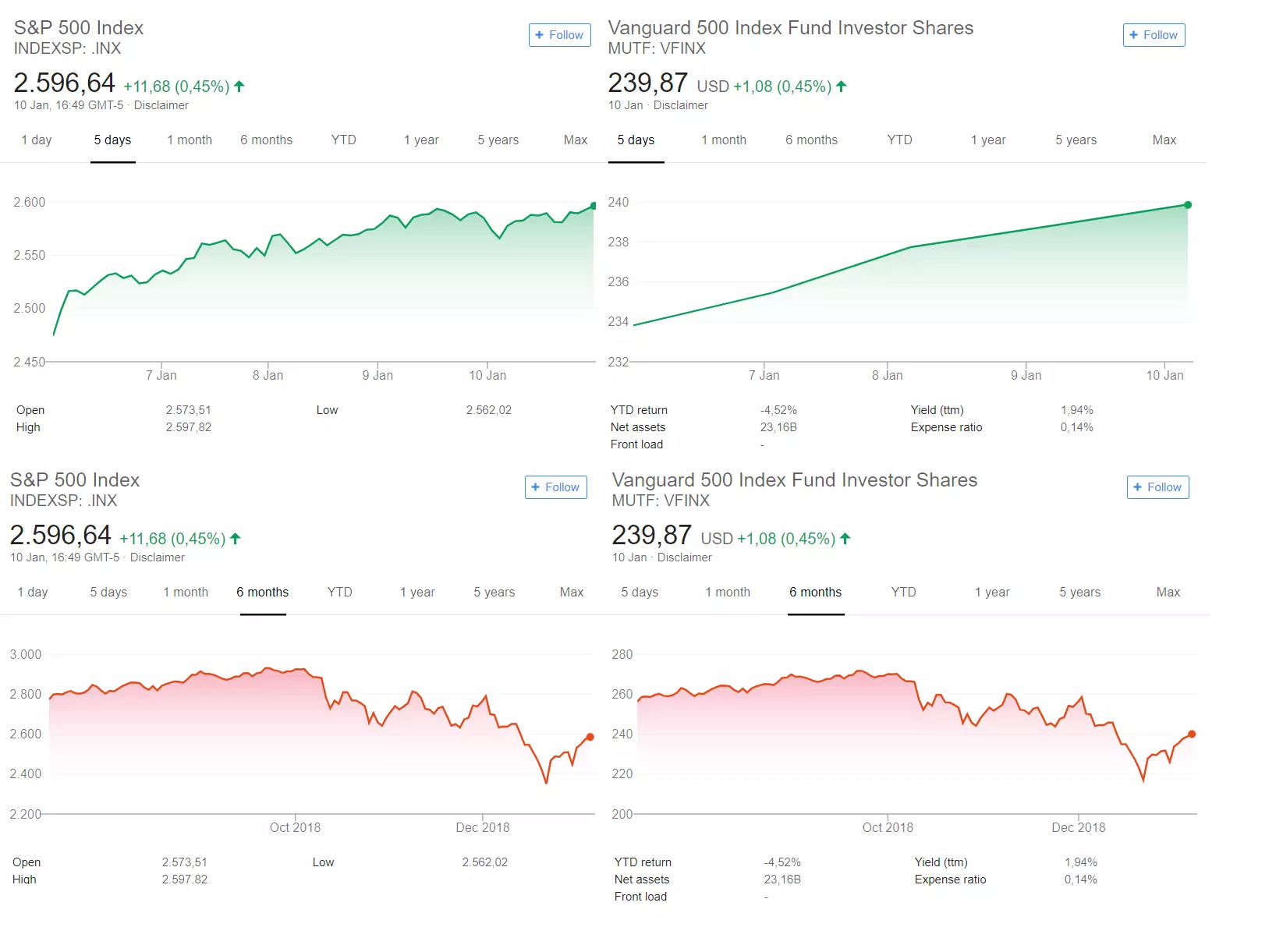

On the picture you can see an example of the performance of the S&P 500 itself (left) and the performance of VFINX – Vanguard’s S&P 500 index fund (right) for 5 days and 6 months. Not the best example to represent tracking errors, as the graphs are pretty similar, so that illustrates to which extend a fund can track its benchmark’s performance.

However, on the 5 day screenshot, you can see that the fund’s price is updated daily, unlike the index’s value. The reason for this is that a fund’s price is determined once per day, after the market closes. The fund’s price is called its Net Asset Value (NAV) and is calculated by the last quoted price of all the fund’s holdings minus the fund’s expenses, divided by the number of outstanding shares.

This shows another difference between investing through mutual funds and buying stocks – you can’t do intra-day trades using funds, as their price is determined once per day and the orders are executed once per day. Some people consider this a disadvantage and some consider it an advantage (preventing them of day-trading). I consider it neither. This is how mutual funds work and the investor’s decisions should originate from his strategy, not from operational restrictions or getting emotional.

Index funds are a great investment vehicle for passive investors looking for a simple way of building their long-term wealth. They also have lower expense ratios than the actively managed funds, simply because there is less staff required for portfolio management and they trade less frequently.

Wrap-up

In any case, before deciding to put your money in an index fund (which is a great idea), you should know which market (index) you want to use as a benchmark for your portfolio. We won’t cover asset allocation in this post, but even if you go to a fund, you’ll need to know whether you want to buy index funds tracking the US market, an international market, an emerging market, etc.

And after you find the funds that you can invest through, make sure to compare their costs. I can’t give a recommendation, as each country has local mutual funds and my audience is not localized, so you should do your research before deciding to invest in a fund.

Let me give you an example: I found a mutual fund that tracked the market I was interested in, but it had >0,2% yearly fee plus enter and exit fees. Since they were only a tracker fund, I could achieve the same performance by simply buying an ETF that tracks the same index (and found one with a 0,07% expense ratio).

Please don’t get this wrong, though. I’m not trying to say that ETFs are “better” than mutual funds. I’m saying that in my specific case (i.e. my investment opportunities based on where I live) I could save a lot more on fees by going that road. If you’re an American, for example, you may go the route of index funds through Vanguard. A few Google searches will show that it comes down to buying and holding VTSAX. I agree, as you’d get complete exposure to the US market, not just the large cap companies, for an expense ratio of 0,04%. Beautiful! But of course, nothing on this blog is investment advice.

However, I mentioned ETFs, but we still didn’t cover what they are and how they work. I’d highly recommend to learn about those too before making any decisions. Actually, I’d highly recommend to learn about ETFs, asset allocation, DCA, taxes, market cycles, and recessions before making any decisions… But then you may regret not starting as early as possible or end up overthinking everything… I’m doing it myself, even at this moment. Never mind…

Subscribe to receive mails each time I publish a new post – and expect the next one covering ETFs soon. Meanwhile, make sure to do your own research on mutual funds as well.

Previous Become an Investor post: Introduction to Index Investing

Next Become an Investor post: ETFs

PayPal.me/MonkWealth

PayPal.me/MonkWealth