Now, when you understood the ultimate market trend and how the economy works, it’s time to learn how to utilize what you already learned. Basically, index investing through index funds and ETFs is the foundation on which we will build the rest of the knowledge.

In case you feel a bit overwhelmed – don’t worry. We’re taking a break here. This post won’t introduce new financial instruments, but will cover how to approach investing using the ones you already know. Basically, we’re beyond the step of covering the basics and we’re slowly moving towards investing strategies.

Before implementing a specific strategy though, you’ll have to know what to invest in. More precisely, how will you distribute your money across the different asset classes you have in mind. This process, as its name suggests, is known as asset allocation and we will dive deep into it in this post.

Asset Allocation

Okay, let’s define what asset allocation means first.

Asset allocation is a wealth distribution strategy that attempts to balance the risk and reward in an investor’s portfolio. This is done by assigning a percentage of his portfolio into different asset classes based on his goals, investment horizon, and, most importantly, risk tolerance.

Asset allocation usually refers to the percentage of the portfolio allocated in stocks versus bonds, but also in stocks, bonds, cash (or cash equivalents), and other asset classes as well.

Asset allocation spectrum

Basically, a stock/bond allocation between 0/100 and 50/50 are considered conservative while the ones with higher stock allocation are considered more aggressive.

90/10 stock/bond allocation would mean that a person can withstand higher risk, but could enjoy higher returns during a bull-market.

50/50 stock/bond allocation would mean that a person won’t be as impacted by market crashes or volatility because he relies on a fixed-income asset as well.

By the way, if you need a reminder on what stocks and bonds are and the risk/reward associated with them, you should re-read the Introduction to Stocks & Bonds post.

Now, let’s see how different factors influence an investor’s asset allocation.

Allocation Factors

Investment Horizon

This is the period in which you plan to be “in the market”. But how does that influence an asset allocation decision?

Well, someone who saves and invests for a 30+ year horizon can afford to take riskier positions than someone who will need the money in 6 months. The former could go high in stocks (100% stocks or 90/10 stocks/bonds) and the latter should keep his money in cash. In the last post we covered why a stock allocation is less risky in the long term.

To sum it up: in the long term, the ultimate direction of the stock market is up.

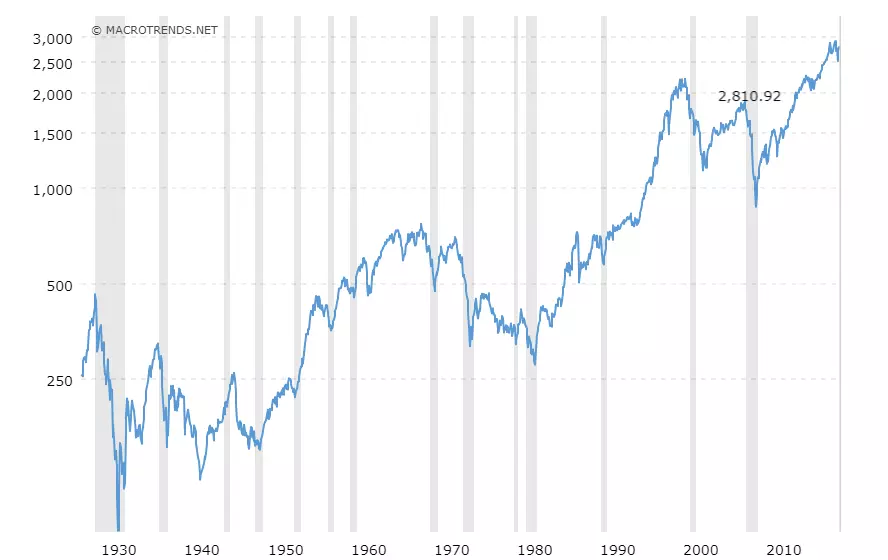

Here is a picture of the S&P 500 from before 1930 until today.

In case it doesn’t look like much, have in mind that it’s a inflation adjusted and with a logarithmic scale. Here is the picture on a linear scale without inflation adjustments.

That’s the nature of the economy. Volatile and unforeseeable through the years, but stable and predictable through the decades. And those grey lines – those are the recessions. We will have a few in the future as well. But unless you’re planning to withdraw money within 5 years (and thus being forced to sell low), you shouldn’t care that much. The market will always recover.

What I’m trying to point out is that a higher stock allocation is safer for someone who has a longer investment horizon (i.e. won’t need the money in near future). On the other hand, a person who plans to retire in 5 years may use a less aggressive allocation, such as 60/40 or 50/50. The bond allocation would make a recession less brutal, would provide sufficient interest payments, and would be used as a source of income until the market recovers.

Now, what about other factors that affect one’s asset allocation?

Risk Tolerance

Risk tolerance is the amount of risk an investor can / is ready to withstand in order to achieve better results. Investopedia defines it as the degree of variability in investment returns that an investor is willing to withstand.

An investor’s risk tolerance is very important because it’s the biggest factor when determining his asset allocation. For example, a person who never lost money and wants to invest 80% of his acquired wealth in the stock market, may have a really hard time (as in: even getting suicidal) when we enter a recession. Imagine how would you feel after working for a decade and seeing your wealth being mercilessly cut in half, while you’re left there with no one to blame but yourself. Really try to envision it.

If the thought scares you – your risk tolerance is low. And that’s perfectly fine. Than means that you should either stay away from the market or minimize your stock allocation. How much? Imagine yourself losing $10k. How does that feel? Find the amount you wouldn’t panic about and do the math accordingly.

I, for example, feel comfortable with my stock/bond allocation, which stands at 100/0 at this moment. In December (2018), my stock portfolio took a hit, but I didn’t panic at all. I knew it will eventually recover and had my emergency fund ready in case I needed some money. And I’m pretty confident that I’ll keep the same mindset even if, sorry, even when, a recession hits.

A random quote you should remember: you only lose if you sell.1

Long story short, the higher your risk tolerance is, the higher your stock allocation should be. So basically, it’s a risk/reward situation and those with lower risk tolerance should look more into bonds and also keep a bigger portion of their savings in cash, savings accounts, or other low-to-no-risk assets.

An almost risk-free way to grow your wealth is putting all your money in a savings account. However, if you’re from a developed country, it will only yield 0,02-0,05% per year, or in other words, up to 50$ for every $100k you have. This rate doesn’t even beat inflation and you should read this post to understand the hidden risk you’re taking when ignoring inflation.

Age based allocation

The concept of age based allocation is pretty popular and the idea behind it is that the stock/bond allocation should be tied to one’s age. The reason for this is that as the person gets closer to retirement (i.e. not relying on a salary anymore), he should be getting more conservative rather than aggressive.

And it makes sense. However, I think that asset allocation is way more personal than using a formula. Nevertheless, this may get you an idea of where you are, or at least point you towards the direction you need to be.

Basically, age based allocation would suggest that you need to have your age allocated in bonds. That would mean that a 30 year old would have an asset allocation of 70/30 stocks/bonds and a 60 year old would have an asset allocation of 40/60.

- A 20 year old would have an asset allocation of 80/20 stocks/bonds;

- A 30 year old would have an asset allocation of 70/30 stocks/bonds;

- A 40 year old would have an asset allocation of 60/40 stocks/bonds;

- A 50 year old would have an asset allocation of 50/50 stocks/bonds;

- A 60 year old would have an asset allocation of 40/60 stocks/bonds;

- A 70 year old would have an asset allocation of 30/70 stocks/bonds;

And so on.

However, different resources recommend different age based allocations, so nothing is written in stone. A few examples are: having a stock allocation of [110 – your age] (so, a 30 year old needs to have 110 – 30 = 80% in stocks and 20% in bonds). This offsets the threshold by 10, but other resources suggest [120 – your age]. The thing I’m trying to convey is that there is no right answer and it doesn’t depend just on the investor’s age.

I watched a Jack Bogle (RIP) interview a few days ago, where he is laughing at the idea of how high his bond allocation should be based on his age. The video is below, but remember that I’m putting it here just for the reference, watching it is not necessary in order to understand asset allocation (the referenced part is around the 9th minute and there is a great segment on lazy portfolios at the 18th):

Let me finish this section with this quote, directly from the Vanguard website:

Asset allocation is the first thing you should consider when getting ready to purchase investments, because it has the biggest effect on the way your portfolio will act.

And remember, there is no “right” allocation! It’s all about what makes you sleep well at night.

Asset Allocation in more detail

We used a stock/bond model to describe how related it is to an investor’s risk tolerance and other factors. However, as we saw in the post about ETFs, we should also have an allocation within the stock allocation. Let me describe what I mean.

Let’s say that you determined your stock/bond allocation. Still, the questions that remain are: which stocks and which bonds?

Stock Allocation

One way to go for the stocks is purchasing an ETF tracking the S&P 500 and be done with your stock allocation. However, not everyone wants 100% of their stock portfolio to be allocated in large-cap US companies. For example, a person might want to have exposure to the total US market and go 40% large-cap, 30% mid-cap, and 30% small-cap companies.

But what about the investor who is not comfortable with only US exposure? This person can track the MSCI World Index and be ~60% in the US market and ~40% across the rest of the developed world (EU, Middle East, and Pacific). More details about it here and here. Another person might might be bullish on his own country’s economy, so he would allocate 70% of his stock portfolio in, for example, the UK (by tracking the FTSE 100).

Another thing to consider is the allocation between developed and emerging markets. An investor can decide to be 80% in the developed countries and 20% in the emerging markets.

There are literally endless options… But none of them is “right”. For example, there is JL Collins who is a big advocate of keeping it simple with VTSAX. There is this Dutch blog which suggest VWRL as a stock allocation. This guy, on the other hand, is bullish on emerging markets. Some bloggers have a more complex allocation, but in my view, the most comfortable way to maintain a lazy portfolio is keeping it simple.

Just to illustrate: my stock allocation is 100% in an ETF tracking the S&P 500 and I’m completely comfortable with it. Historically, the world’s economy reacts to how the US economy moves. So I’m aggressive enough to be 100% in stocks, but conservative enough not to go into emerging markets or high-yield dividend stock allocation etc. I may revisit this in the future, though.

By the way, same goes for bonds. An investor can choose his allocation between government bonds, corporate bonds, and the distributions within each (which countries, which companies, etc.).

More asset classes

Let’s see the bigger picture once again and add more asset classes to the equation. As mentioned previously, we took a stock/bond allocation for the sake of simplicity, but an investor’s asset allocation is not necessarily just in stocks and bonds. Take a look at the following allocation:

US Large Cap – 15%, High-yield stocks – 5%, EU Small Cap – 7%, Emerging Markets – 3%, US Government Bonds – 8%, EU Corporate Bonds – 2%, Real Estate – 20%, REITs – 10%, Angel Investments – 15%, Cryptocurrency – 5%, Certificates of Deposit – 7%, and Cash (emergency fund) – 3%.

We can still boil it down to stocks, bonds, real estate, riskier investments, and cash, but I just wanted to point out that asset allocation can go way beyond stocks & bonds. And I know that this might be overwhelming if you’re new to investing. But don’t worry, this is not something you need to come up with right away, or even ever. I’m just giving an example of the possibilities – and there are plenty of other investment opportunities beyond the ones mentioned.

But don’t try to learn everything about everything in advance. Cover the basics and let experience be the teacher.

By the way, there may be two new terms in the list: REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts, companies that own and manage real estate to produce income) and Angel Investing (providing capital for a start-up in exchange for ownership).

Anyway, the thing you should consider now are your goals, investment horizon, and risk tolerance – how much of your hard-earned money are you willing to risk in order to achieve better returns on your investment.

Conclusion

So, you may be disappointed that I didn’t say how exactly should you allocate your money. You shouldn’t.

Never forget that there is no right allocation that works for everyone and an investor’s portfolio should represent his own personal situation. Everyone willing to start is responsible for evaluating their goals, determining the term for which they are investing, and understanding their own risk tolerance. Understanding these factors is the key to coming up with an adequate allocation.

The goal of this series is to guide you to become an investor, not just giving away free or potentially inadequate advice.

Anyway, an approach that can work well for many people is keeping an emergency fund (or as much cash as you wouldn’t like to risk) and going with 80/20 stocks/bonds with the rest, with the majority of the stock allocation in large cap companies (S&P 500). But the decision is up to the investor.

So, let’s say you found your allocation. The next question is: how to manage it? What to do once you determine it? How should you invest your money? How often? How much? What if an asset class underperforms and another one goes to the moon, thus hinders the initial allocation?

There is still so much to learn… But not in the post about asset allocation. In the next post in the Become an Investor series we’ll discuss different investment strategies and how you can rebalance your portfolio.

I’ll just stop here and see you in Part 8.

Previous Become an Investor Post: Bulls, Bears, Market Cycles, and Recessions

Next Become an Investor Post: Investment Strategies (Lump-Sum vs DCA)

PayPal.me/MonkWealth

PayPal.me/MonkWealth

Good stuff, Monk!

As you might know, I’m not a huge fan of the stock market. I still believe it’s better to Invest in index funds, than to not Invest at all – but I think history clearly shows us that there are no guarantees.

I aim at retiring no later than when I’m 60 years old (in 25 years). Ideally however, I would like to retire a lot earlier than that though – when I’m 50 (in 15 years). So let’s imagine a scenario, where I Invest everything I own in a broad index (during the next 15-25 years).

Using your Graphs from S&P 500, now imagine that it’s 1955. I’m planning to retire in 25 years (that would then be in 1980). If I had invested all my savings in an S&P 500 tracking index (from 1955->1980), I would be no better off than I was in 1955!

Now imagine that it was 1994, and I was retiring in 15 years (that would then be in 2009), which is kind of like the scenario I currently find myself in. Same thing can be said for this period – my growth would be equal to 0%, after 15 years…

Us FIRE people might have a long Investment strategy (30+ years), but if you’re planning to retire in LESS than 20 years (which most people in their mid/late 40’s would), there’s absolute no guarantee that the stock market will be a good Investment (as history clearly tells us).

I’m not saying you should’nt Invest in the stock market – I’m just saying that counting on that 8% yearly growth (which seem to be norm) is really not that safe…

So again like you say, the number one lesson you should learn as an investor, is diversification across asset classes (in my humble opinion).

Thanks Nick!

Indeed, I have these thoughts as well, especially when I see the S&P 500 graphs on a larger scale. Figuring it all out is hell of a challenge. 🙂

Also, similar to you, I’m in the category that aims to be FI in less than 20 years, so I often run scenarios like the ones you mentioned (retiring before the dot-com crash, surviving the housing crash, and start seeing gains after a decade). The best hedge, as you mentioned, is diversifying across asset classes as well – and since every investment has an inherent risk, the broader the diversification, the better. I’d still keep the majority of my portfolio in stocks, but wouldn’t fully rely on it. Another one is having an income stream decoupled from a job. I think that any person planning to RE should consider both.

That being said, we need to remember that the scenarios we mentioned are lump sum investments at an extremely wrong time. DCAing for 5 year before a recession will make the value of the portfolio much higher before a market crash. DCAing after (or during) a recession will make a portfolio grow faster. I’m not saying that there are no other risk than investing a lump-sum on the peak, but that particular risk can be avoided by DCA and planning the retirement accordingly (as in: continue working until the next bear market and reevaluate). This is where risk tolerance is a factor.

Lastly, we should remember that not everyone who invests is aiming to retire early. Asset Allocation is a concept that’s independent of FIRE and, as you also said, having the surplus in index funds / ETFs is better than not investing at all.

It’s very true that DCAing would obviously mitigate some of that dip-risk 😉

BTW: 0,70% bank interest rate here (Bank Norwegian!) 😛

Santander Consumer bank has a 0,80%, but you’re Money is “bound” for 30 days. So I use Norwegian for my primary Cash stash.

I like that you hoard Cash too like I do atm! 😛

That interest rate is not that bad for a risk-free return in a stable country. 🙂