This is the second post of the Supply and Demand Series.

In the first post, Supply and Demand – an Introduction, we explained supply and demand curves, equilibrium price and quantity, and aggregate supply and demand.

In this post we’ll understand what consumer surplus and producer surplus are.

Reminder

Let’s set the stage first.

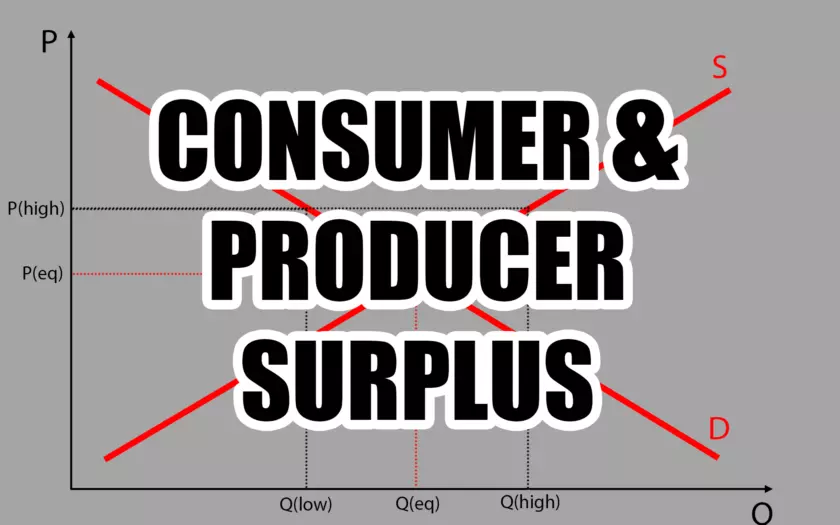

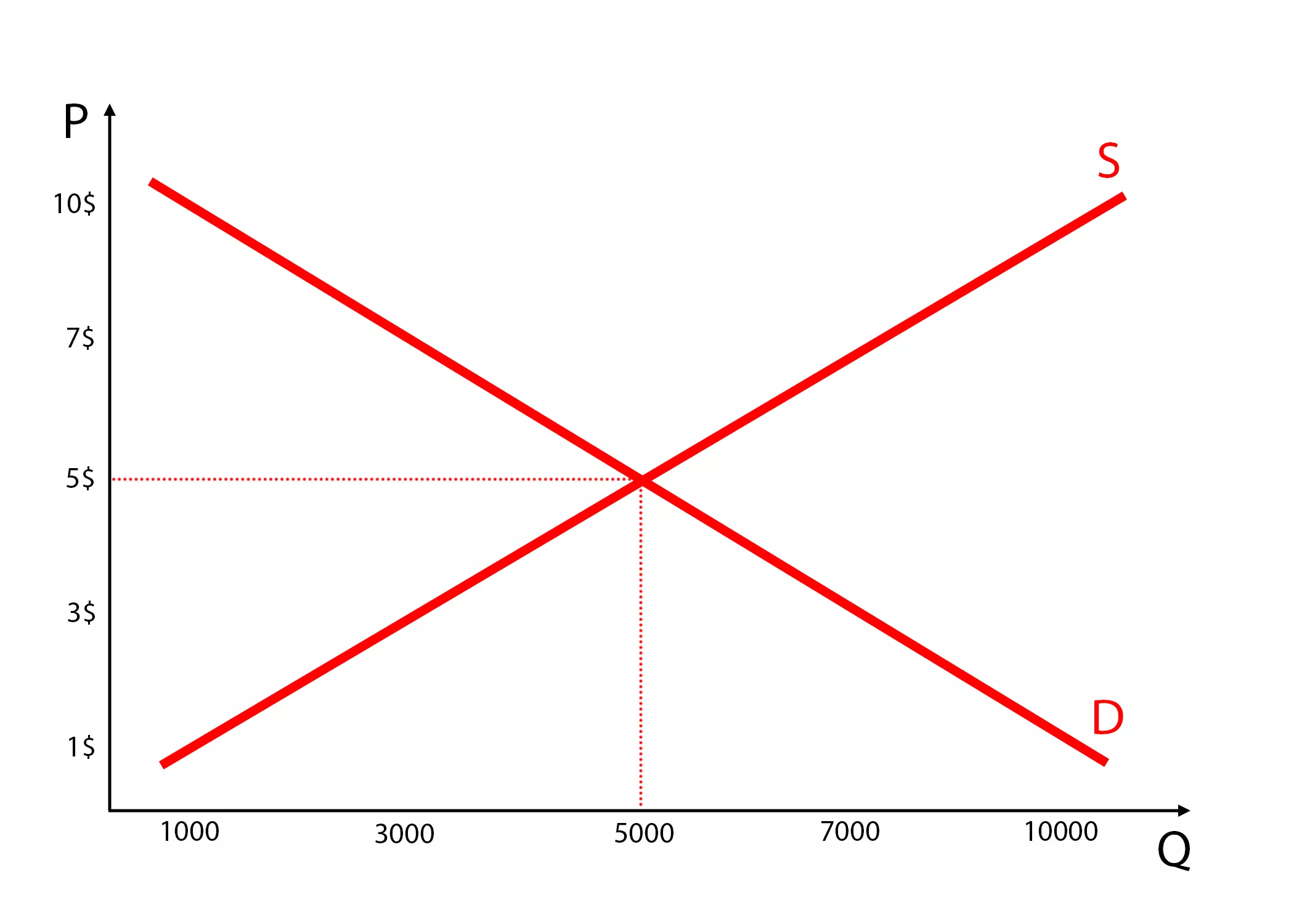

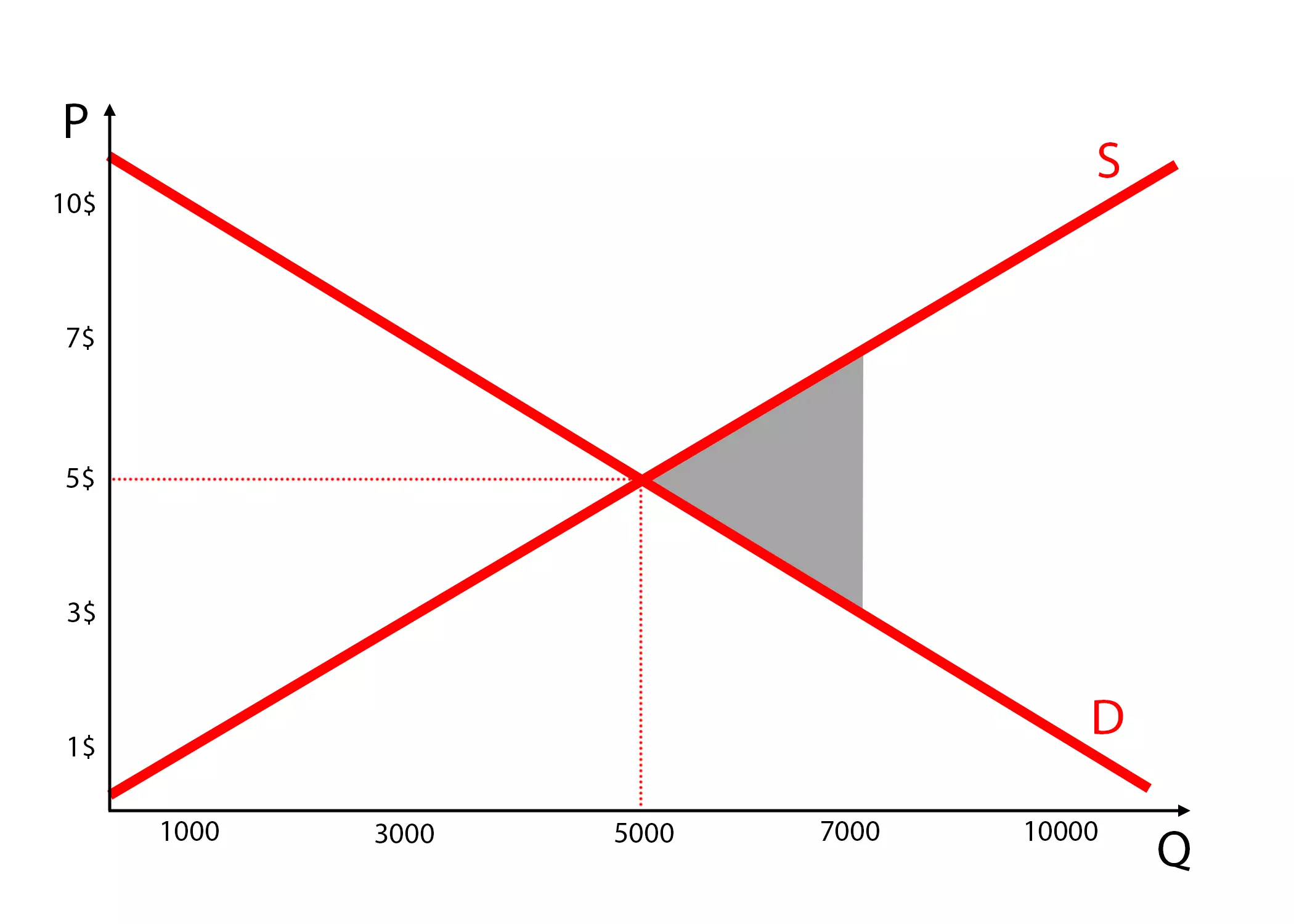

Here are the supply and demand curves for a certain good X.

As we can see in the picture, the equilibrium price is 5$ and the equilibrium quantity is 5000.

However, if we take a look at the demand curve, we see that there is a portion of the population that are willing to buy the product for the high price of 10$ – shown by the top most point on the demand curve. On the opposite side, there are consumers who’d buy larger quantities of the product, but only if it was 1$.

This is the law of demand in action.

From the suppliers perspective, we see that certain suppliers would produce the product even if the selling price is 1$, but in smaller quantities. On the other side, if the price of X is higher, more producers will be willing to produce it.

This is the law of supply in action.

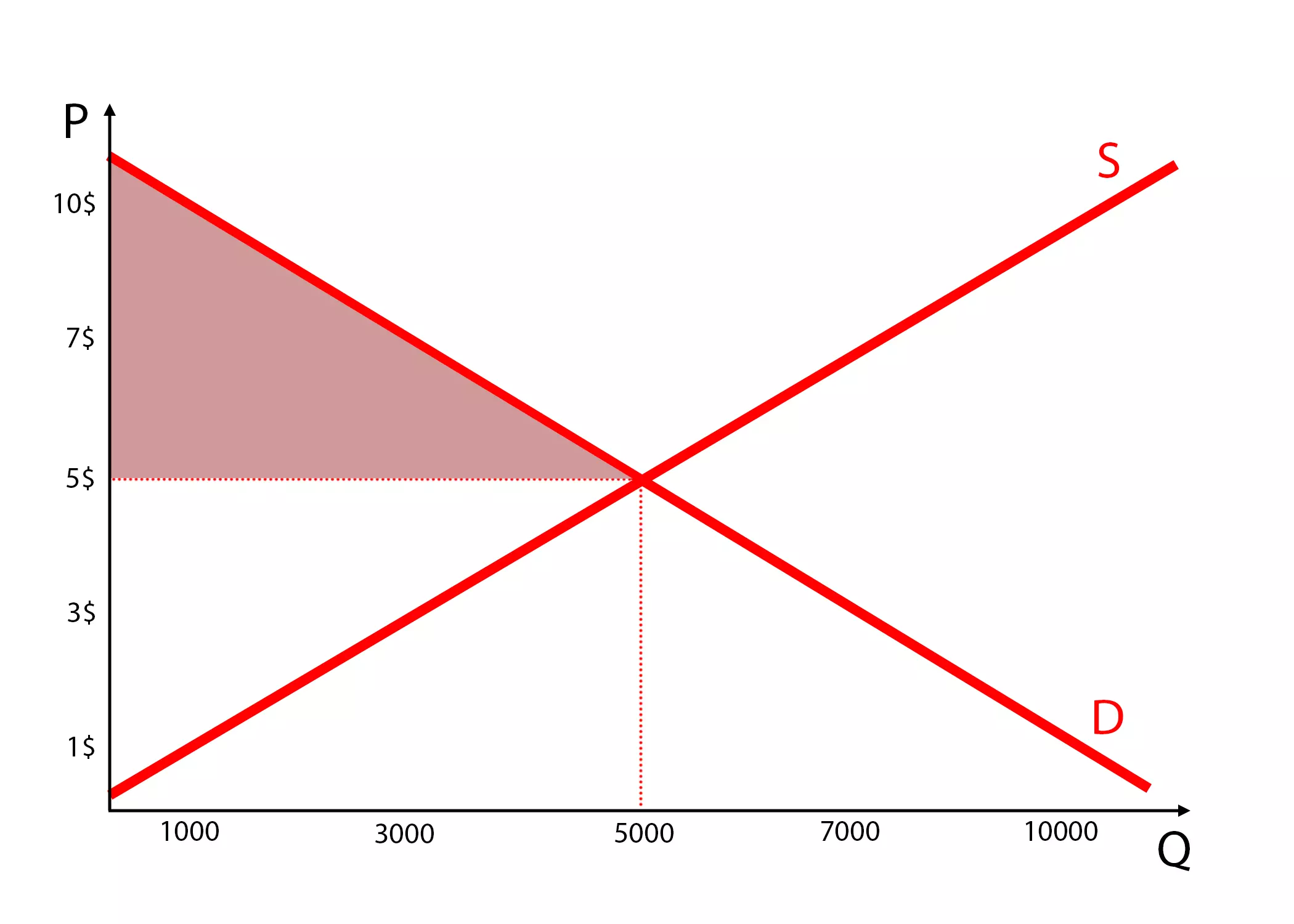

Consumer surplus

Consumer surplus is the difference between the total value the consumers get out of the units of the good they buy and the total amount they need to pay to buy those units.

I understand this might be a bit confusing, so let’s turn back to our example of the good X.

Based on the demand curve, we know that there is someone out there who is willing to pay 10$ to buy X. However, he bought the product for 5$ – the price set by the market forces. The difference between the value that X has to him (10$) and the amount he paid to acquire it (5$) is the consumer surplus.

The grayed out area represents the total consumer surplus.

In simpler terms, it’s the surplus value a consumer gets relative to the purchase price.

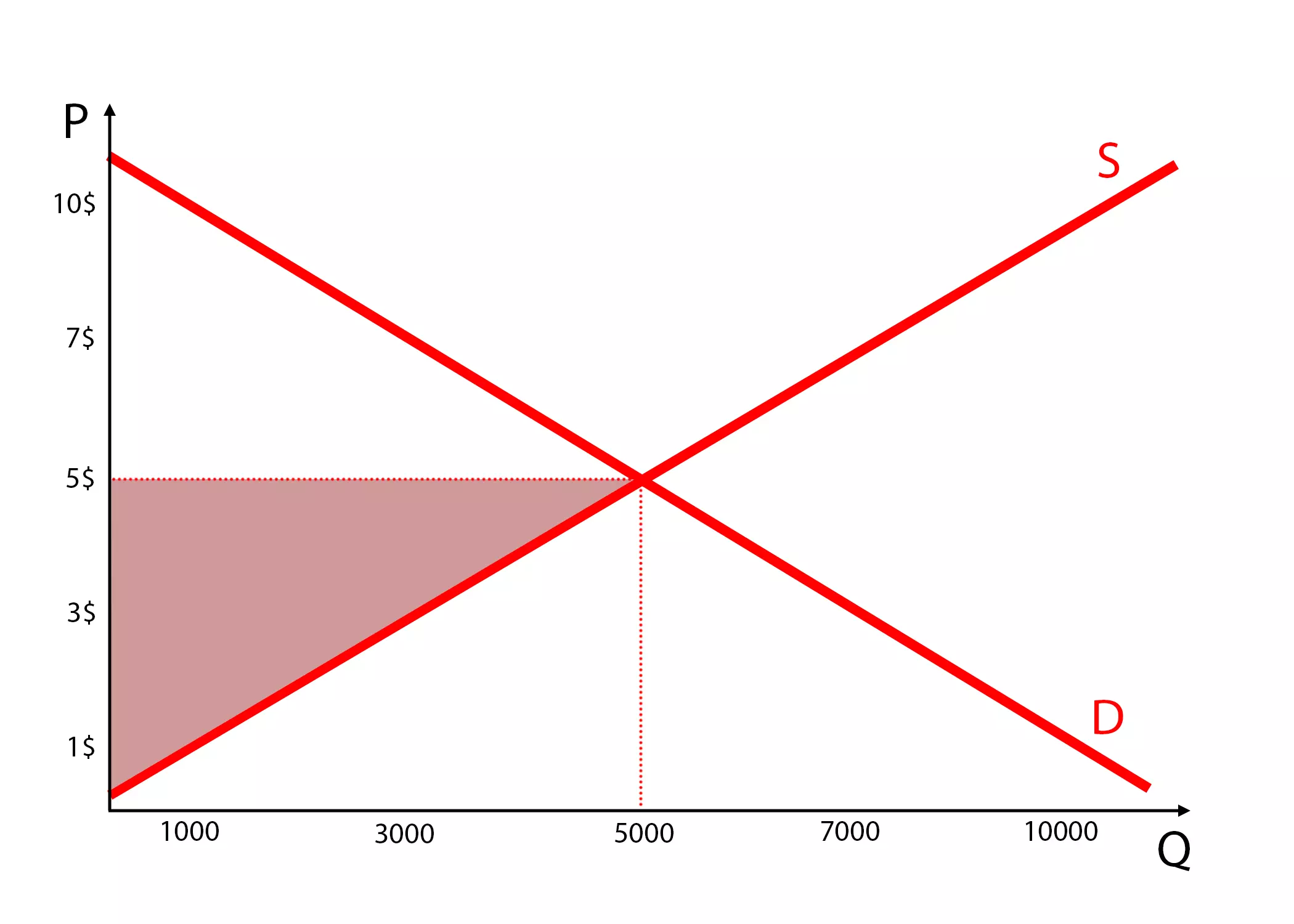

Producer surplus

Producer surplus is the difference between total revenue (TR) suppliers earn by selling a certain number of units and the total variable cost (TVC) of producing those units.

Similarly as we did for the consumer surplus, let’s follow up with an example.

If we take a look at the supply curve above, we see that there are producers whose TVC is quite low and thus are willing to sell X for only 1$. However, they’ll sell the product for 5$ – the price set by the market forces. The difference between the selling price (5$) and the price of producing those units (up to 1$) is the producer surplus.

The grayed out area represents the total producer surplus.

In simpler terms, it’s the surplus the producers get when selling a product for more than they value it.

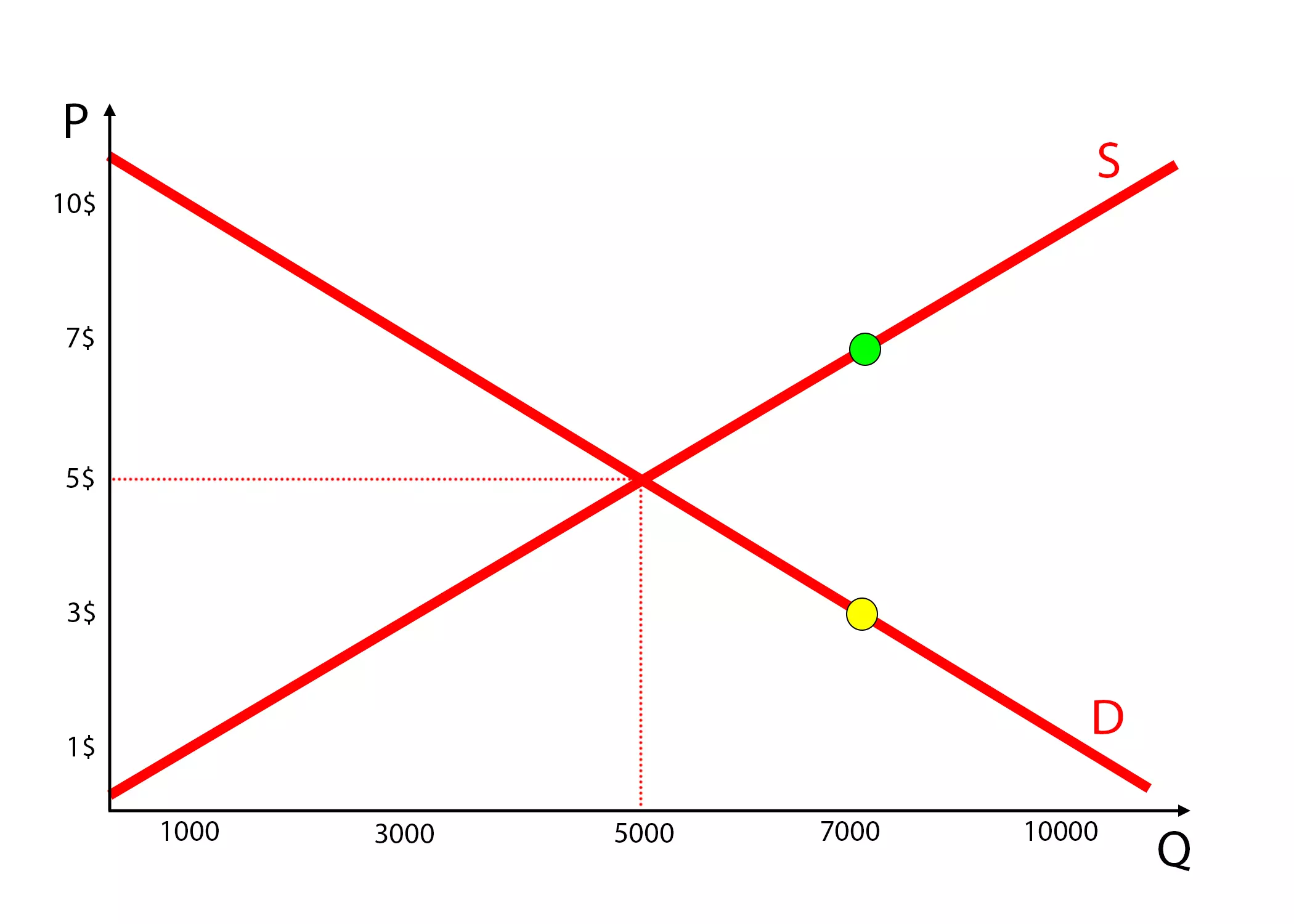

Total surplus and benefit to society

The combined amount of producer and consumer surplus is called the total surplus.

It’s shown in the grayed out area below.

The combination of consumers and producers trying to maximize the surplus leads to the efficient allocation of resources of producing X because it maximizes the total surplus, or total benefit to society, from producing X.

Let’s understand why is that so.

Look at the graph and see what happens with the consumer who is willing to buy X for a price of 3$ (the yellow dot on the demand curve)?

Nothing happens.

This consumer doesn’t value X enough in order to purchase it for the high price of 5$ set by the market.

Now, let’s see what happens with producers who have high TVC or high opportunity cost of creating X. For example, someone who’s willing to sell the product for 7$ (the green dot on the supply curve).

Have a guess.

Exactly – nothing happens as well.

Their cost of producing X is so high that they can’t afford to sell it at the market price of 5$ and thus they’re not participating in the market.

The total surplus will be maximized when the resources used for producing X satisfy most of the society. This is achieved by maximizing total surplus.

Let’s see why including these participants in the market would lead to inefficiencies.

Deadweight loss

Deadweight loss is the reduction in consumer surplus and producer surplus due to overproduction and underproduction.

Don’t worry if it sounds confusing, as the examples usually have you covered.

If producers decide to produce 7000 units of X and sell them for the price of 7$ determined by the law of supply, there won’t be enough consumers willing to pay that price for the product, creating an inefficient allocation of resources.

The deadweight loss created due to overproduction is the grayed out area in the picture below.

On the other hand, if producers produce only 1000 units of X there will be a bigger portion of the population which won’t get the product, but also the revenue won’t be maximized.

The deadweight loss created due to underproduction is the grayed out area in the picture below.

If we generalize a bit, we can see that both overproduction and underproduction lead to inefficient allocation of resources that doesn’t maximize consumer and producer surplus and thus the benefit of society.

And, as explained in the supply and demand post as well, any deviation will be pushed back to the equilibrium by the market forces. If there is shortage in the market, more suppliers will join to profit from the existing demand, bringing the price and quantity supplied and consumed to equilibrium. If they eventually overproduce, less consumers will be willing to buy at a high price, so the sellers will be forced to decrease the supply, again, ending at equilibrium.

The markets are amazing and also efficient in allocating resources and setting the price.

What can go wrong?

This is how beautiful the free markets can be.

The prices are set by the market itself, anyone who values goods and services enough benefits from them, society’s benefit is maximized…

But then… There is the government.

Taxes, quotas, price ceilings… And it all becomes inefficient.

I’ll explain how government’s interference destroys everything it touches in the next Supply & Demand post.

And if you don’t want to miss it, make sure to subscribe to get a mail each time I publish a new post.

Until next time, I’d appreciate a share on social media.